Ensuring safer future drugs

Researchers also believe that elucidating the mechanisms of the drugs will help ensure safer future treatments. Most drugs have side effects, and lecanemab and donanemab are no exception. Some people who were given the drugs during clinical trials were found to have swelling or microbleeds in the brain in response to treatment – known as Amyloid Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIA). The majority of people who experienced ARIA had no symptoms, but in rare cases, more severe symptoms and complications occurred.

Prof Bart De Strooper, Group Leader at the UK DRI at UCL, explains:

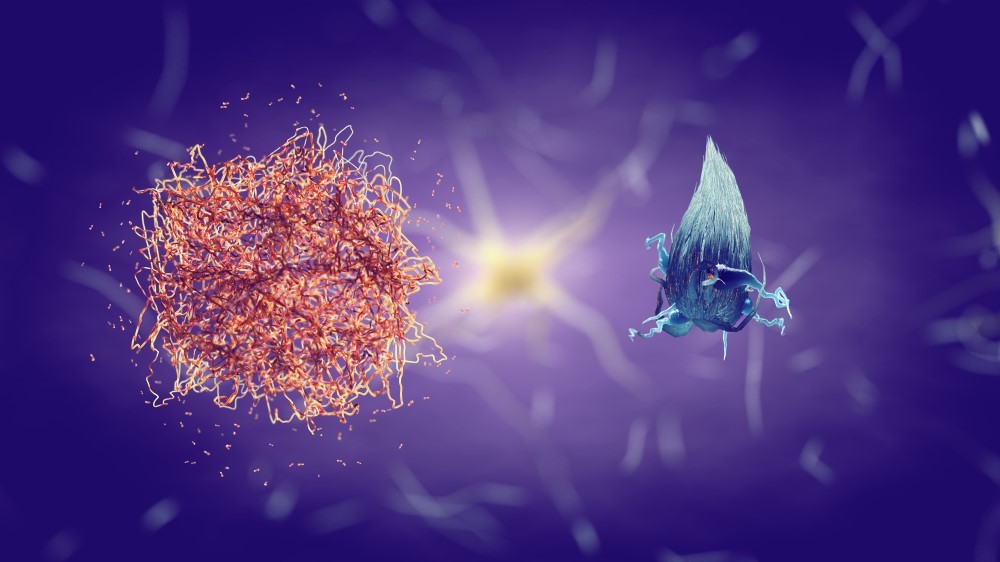

“We still don’t understand how these antibodies actually clear amyloid. Unlocking this will help us understand exactly why side effects occur, and we may then be able to mitigate them.”

Detecting the disease earlier

If there is one thing scientists agree on, it is that early diagnosis is essential to ensure people who would benefit from treatment can start being treated before Alzheimer’s begins to cause extensive, irreversible damage to the brain.

“By diagnosing earlier, you might be able to treat people before amyloid starts to build up in their blood vessels, and avoid ARIA,” Prof Hardy explains. “So early diagnosis might also help reduce side effects.”

However in reality, if lecanemab and donanemab were approved for use in the UK, people with dementia would face a significant wait to access them. Most people receive a dementia diagnosis from a psychiatrist in a memory clinic. According to Alzheimer’s Research UK, only 6% of these services fully meet the clinical guidance for diagnostic testing.

At the UK DRI, work is ongoing to develop new diagnostic tools. In the UK DRI Biomarker Factory, work led by Prof Henrik Zetterberg and Dr Amanda Heslegrave seeks to develop blood biomarkers – markers of disease that can be detected via a blood test. Prof Valentina Escott Price (UK DRI Group Leader) is leading work on polygenic risk scores – genetic tests that provide information about an individual’s risk of developing a disease. Together, these new tools could help deliver accurate, earlier diagnosis of Alzheimer’s in the general population.

Easier ways to administer treatment

The drugs are currently administered by intravenous (IV) infusion, which needs to be given every two weeks in a specialist clinic. Trials are ongoing to develop easier ways to deliver the drug – for instance, subcutaneously, meaning an injection into the layer of tissue below the skin. This, Prof De Strooper explains, could make the process simpler and more scalable.

“I think we need to be practical and pragmatic,” he says. “We need to ensure we get the maximum benefit out of these expensive drugs, and one way to do that is to try and get easier ways to deliver them.”