It was recently announced that an international trial investigating the potential of two drugs to slow memory loss and cognitive decline has failed to benefit people with a rare, inherited form of Alzheimer’s disease. The researchers will continue to analyse data and are hopeful that insights gained can inform future clinical trials in this area.

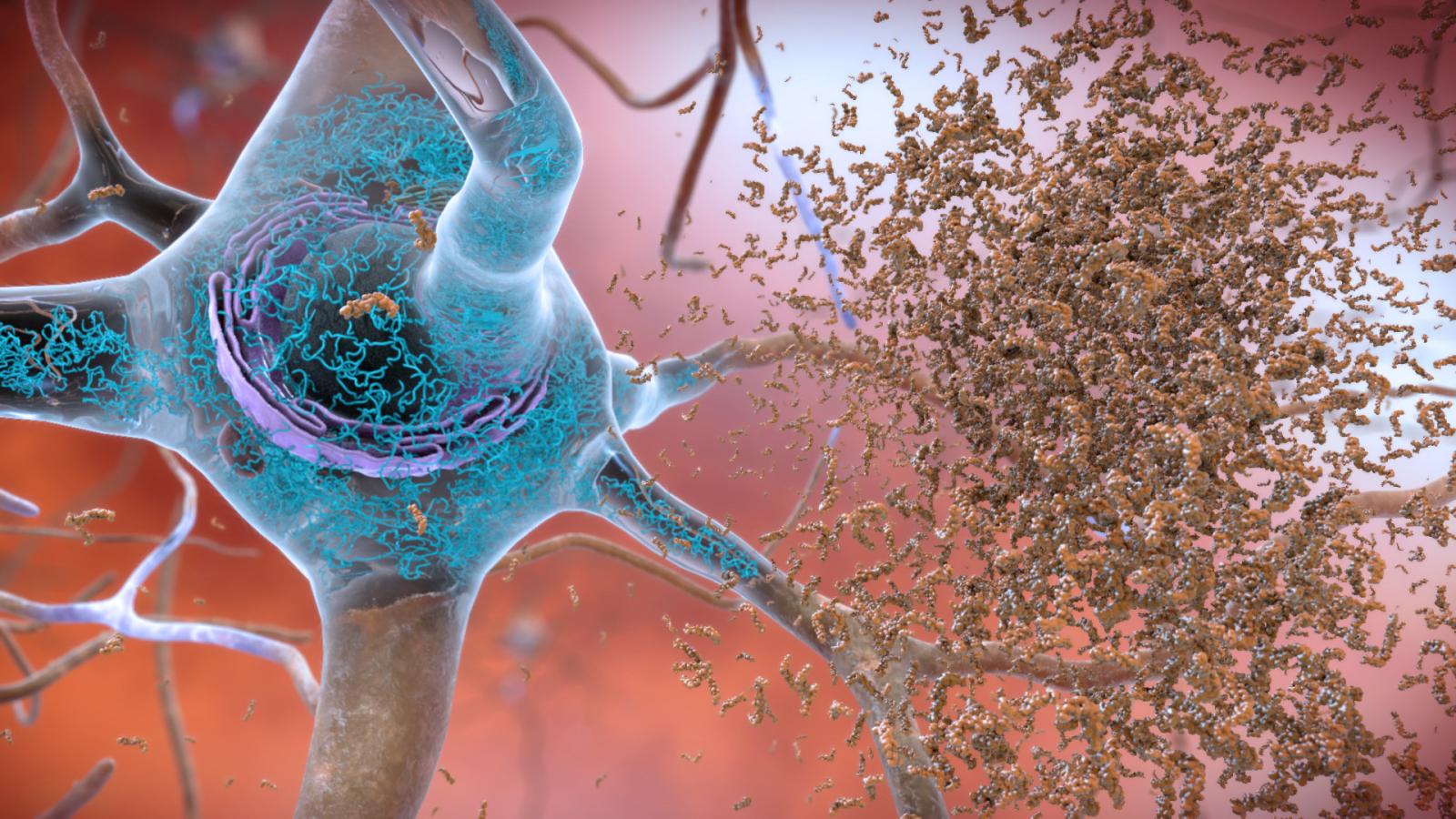

The phase 2/3 trial led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis through its Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network-Trials Unit (DIAN-TU), aimed to separately evaluate two drugs, solanezumab, made by Eli Lilly and Co., and gantenerumab, made by Roche and its US affiliate, Genentech - both of which act on amyloid beta. The accumulation of this protein in the brain is thought to represent one of the earliest events in Alzheimer’s disease and a viable target for treatment.

But in failure, there is always progress.Prof Bart De StrooperUK DRI Director

With harmful biochemical brain changes thought to occur decades before symptoms arise in Alzheimer’s disease, there has been a drive to position intervention earlier in the disease process for maximum benefit. A subset of people with the disease have an inherited, early-onset form where symptoms involving memory and thinking can strike as early as their 30s. With the high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and easier identification with genetic screening, trials are now recruiting this subset to test treatments earlier with the hope that success could improve the lives of these individuals.

A more detailed analysis of the trial’s data will be presented in April at Advances in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Therapies annual meeting in Vienna, followed by presentations at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Amsterdam in July.

Prof Bart De Strooper, UK DRI Director, who was not involved in the study, said:

“It is hugely disappointing for everyone when trials targeting dementia do not meet our expectations. The DIAN-TU trial focused on those carrying mutations that cause changes in amyloid beta generation. That anti-amyloid treatments did not yield a positive result in this population reaffirms that our understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease is too simplistic. Scrutiny of the data is now required, and in the coming months we will be better placed to determine whether targeting amyloid beta is a non-starter, or whether we need to rethink the particular treatment approach.

Either way, this is a setback for viable Alzheimer’s disease therapies and highlights the pressing need to invest and explore other avenues. But in failure, there is always progress. This research has already been tremendously informative and the collaborative effort involving academia, the pharmaceutical industry, patient-advocacy groups and many more, should be applauded. It is only by working together that we will make significant positive steps for people affected by these devastating diseases.”

For more information on this announcement please see the News release from Washington University.

Image courtesy of National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Article published: 11 February 2020