What is frontotemporal dementia?

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), also commonly known as Pick's disease, is an umbrella term for a group of dementias that mainly affect the front and sides of the brain (the frontal and temporal lobes), which are responsible for personality, behaviour, language and speech.

It is an uncommon type of dementia that affects around one in 20 people with a dementia diagnosis1. Unlike other types of dementia, memory loss and concentration problems are less common in the early stages.

There are three main types of frontotemporal dementia: the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA) and non-fluent variant primary progressive aphasia (nfvPPA). The latter two sub-types both primarily affect language but in different ways.

In clinical terms, there is also a lot of overlap between these main variants of frontotemporal dementia and motor neuron disease (MND) – meaning the conditions are quite similar in many ways.

Frequently asked questions

- How common is frontotemporal dementia?

Dementia mostly affects people over 65, but frontotemporal dementia is more likely to start at a younger age. Most cases are diagnosed in people in their 40s, 50s and 60s, although it can also affect younger or older people2.

Like other types of dementia, frontotemporal dementia tends to develop slowly and get gradually worse over several years3.

- What are the signs and symptoms of frontotemporal dementia?

Frontotemporal dementia usually causes changes in behaviour or language problems at first. These symptoms come on gradually and slowly worsen over time. Eventually, most people will experience problems in both of these areas. Some people also develop physical problems and difficulties with their mental abilities, although unlike in more common forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer's, memory problems usually only occur later on.

Signs of frontotemporal dementia can include:

- Personality and behaviour changes: Acting inappropriately or impulsively, appearing selfish or unsympathetic, neglecting personal hygiene, overeating, craving sweet foods or drinking too much alcohol, showing repetitive or obsessive behaviours, or losing motivation. These symptoms are most commonly seen in the behavioural variant (bvFTD).

- Language problems: Speaking slowly, struggling to make the right sounds when saying a word, or getting words in the wrong order (nfvPPA), or using words incorrectly and having difficulty understanding words (svPPA).

- Problems with complex mental abilities: Struggling with planning and organisation, or having difficulty making reasoned judgements or focusing on tasks

- Physical problems: Moving slowly or stiffly, having difficulty swallowing, losing bladder or bowel control (usually not until later on), or experiencing muscle weakness

These symptoms can make daily activities increasingly difficult, and the person living with the condition may eventually be unable to look after themselves.

More information about symptoms can be found on the Alzheimer’s Society and Dementia UK websites.

- How is frontotemporal dementia diagnosed?

As with many health conditions, individual experiences of frontotemporal dementia can look different from person to person. However, if you or someone you care about is experiencing similar symptoms, please contact their GP for an initial assessment.

If the GP thinks the symptoms could be caused by a form of dementia, they will refer the individual for a specialist assessment.

In some people, frontotemporal dementia can be confused with other conditions in which there are problems with behaviour (for example, some psychiatric disorders) and with other dementias. When diagnosing behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), a doctor will assess behaviour and cognitive functions (aspects of thinking).

The doctor will often arrange blood tests and an MRI or CT brain scan to help confirm the diagnosis and to rule out other conditions. Brain scans can show the loss of brain cells caused by frontotemporal dementia, but there is no single test that can diagnose frontotemporal dementia with complete reliability.

- What treatments are available for frontotemporal dementia?

There is currently no frontotemporal dementia cure or any treatment that will slow it down, but there are treatments that can help control some of the symptoms, possibly for several years:

- Medications: In certain cases, a group of antidepressant medications (known as SSRIs) may help manage some of the behavioural symptoms and mood changes. Neuroleptic drugs, more commonly known as antipsychotic medication, have been used in some patients to treat more severe behavioural symptoms but often have limited benefit and are associated with a significant risk of side effects including the development of Parkinson’s-like movement problems and deterioration in thinking4.

- Therapies: Physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech and language therapy for problems with movement, everyday tasks and communication have all been found to be beneficial for people with frontotemporal dementia.

More detailed information on the different treatment options for frontotemporal dementia can be found on the NHS, Rare Dementia Support, Dementia Research or AviadoBio websites.

- How can I get involved in research and trials for frontotemporal dementia?

We recommend visiting the Join Dementia Research website. It’s a national service that connects volunteers with researchers who are looking for people to take part in their studies and includes opportunities for both people living with dementia and healthy individuals to contribute to research.

- Support for frontotemporal dementia

Support is crucial, not only for those living with frontotemporal dementia, but also for their families and carers. Local dementia support groups, charities and online communities can offer valuable help and friendship as well as activities such as memory cafés and drop-in services. For more detailed information, see our dementia support page.

What are the causes of frontotemporal dementia?

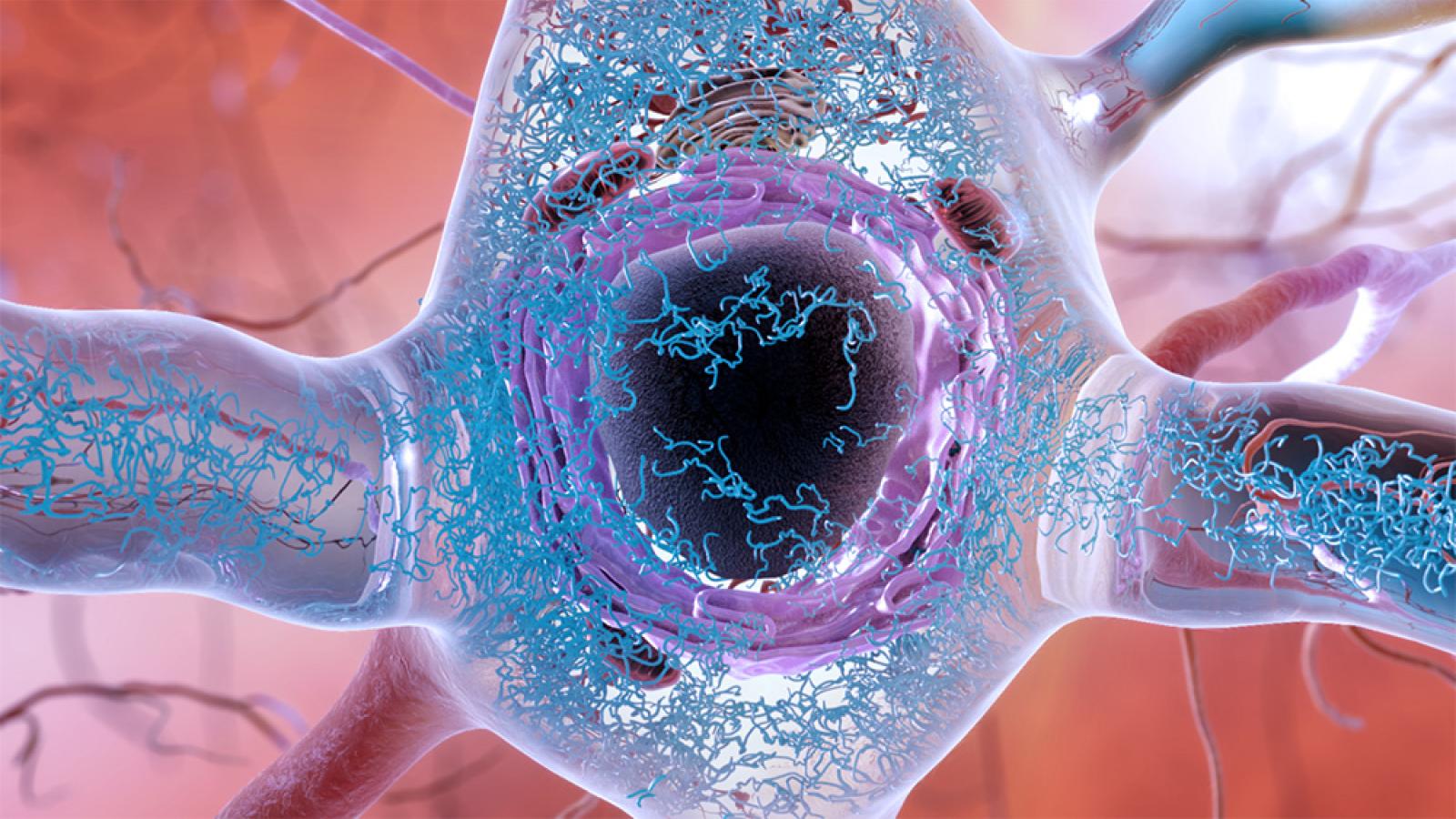

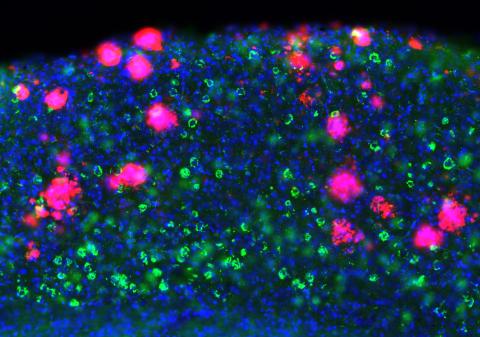

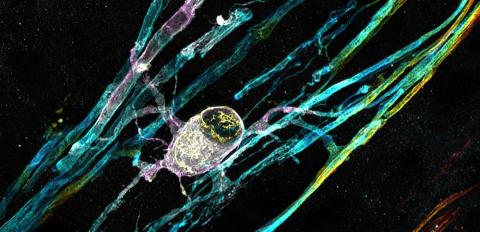

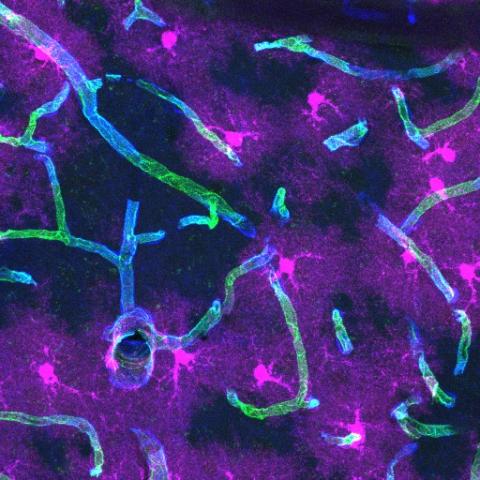

During frontotemporal dementia, clumps of abnormal protein, including tau, TDP-43 and FUS form inside brain cells. These are thought to damage the cells and stop them working properly. This causes the connections between the cells and other parts of the brain to break down. The levels of chemical messengers in the brain also reduce over time. These messengers allow nerve cells to send signals to each other and the rest of the body. The proteins mainly build up in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain at the front and sides. These are important for controlling language, behaviour, and the ability to plan and organise. As more and more nerve cells are damaged and die, the brain tissue in the frontal and temporal lobes starts to get smaller.

It is not fully understood why this happens, but in around 30-40% of cases, a person with frontotemporal dementia has a family history of the condition in which a parent or sibling has been affected2. In these cases, the cause of frontotemporal dementia is likely to be genetic. However, most cases of frontotemporal dementia do not have a genetic basis.

There is a lot of research being done to try to improve understanding of the causes of frontotemporal dementia so that treatments can be found. Many of our UK DRI researchers who work on frontotemporal dementia also work on MND/ALS, because they share the most commonly found genetic mutation.

Frontotemporal dementia and motor neuron disease (MND)/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are clinically distinct neurodegenerative diseases, but the discovery that they share a common cause – an expansion of a six-letter DNA sequence within the C9orf72 gene – is helping to revolutionise our understanding of the diseases.

Scientists are studying the biological impact of the faulty version of the C9orf72 gene to work out the mechanisms that lead to frontotemporal dementia and MND/ALS, including how the resulting protein may not function properly and/or could be toxic to neurons.

For example, Prof Adrian Isaacs is investigating the underlying molecular mechanisms behind C9orf72-related frontotemporal dementia and MND/ALS using a variety of experimental techniques and model systems. He is also developing high-throughput screening approaches to identify genes and small molecules that modulate C9orf72 and other frontotemporal dementia/MND/ALS genes. The ultimate goal is to develop innovative treatment strategies – such as novel gene therapies.

Clumps of abnormal protein (in blue), including tau, TDP-43 and FUS form inside neurons during frontotemporal dementia. Credit: NIH.

Latest news