What is Parkinson's disease?

Parkinson’s disease (or just 'Parkinson’s') is a chronic neurological disorder which slowly progresses, leading to symptoms including tremors and movement stiffness. Around 153,000 people live with the condition in the UK1, making it one of the most common neurodegenerative conditions in the country.

Although there is currently no cure for Parkinson’s, the symptoms can usually be managed with medication and therapies, which can improve quality of life.

Parkinson’s is primarily characterised as a movement disorder, but most people affected by the condition will eventually develop Parkinson’s dementia. Parkinson’s dementia is a subtype of Lewy body dementia. For more information, visit our page on Lewy body dementia.

Frequently asked questions

- How common is Parkinson's?

1 in 37 people alive today in the UK will be diagnosed with Parkinson’s in their lifetime and by 2030, 172,000 people are expected to be diagnosed with the condition1. Worldwide, around 10 million people live with the condition.

Parkinson’s mainly affects people over the age of 50, however, about 10-20% of people with Parkinson’s experience symptoms before this age. This is known as ‘young onset Parkinson’s disease’ (YOPD)2.

- What are the symptoms of Parkinson's?

The symptoms of Parkinson’s vary significantly between individuals and typically develop gradually. They may include a combination of physical symptoms (also known as visible or motor symptoms) and cognitive/mental health symptoms (less visible or non-motor symptoms). However, some symptoms are more common than others, and most people diagnosed with the condition will experience the following to some extent:

- Tremors: These affect 70% - 80% of people with the condition. Most of the time, tremors are not debilitating and can pass after a short time. Tremors occur most commonly in the hands and feet but can also happen in the jaw or tongue or internally. Tremors can be one of the first symptoms of Parkinson’s.

- Muscle rigidity: Stiffness in the limbs, neck or trunk can prevent people with Parkinson’s from moving freely. Muscle rigidity can affect all aspects of life, including eating, walking and moving around the home. This is a common early symptom of the disease.

- Anxiety and depression: Up to half of people with Parkinson’s will experience depression, and up to 40% will experience an anxiety disorder3. Anxiety and depression can be caused by changes in brain chemicals as a result of the condition, and are not always just a reaction to having Parkinson’s. However, living with this condition can be very challenging on people’s mental health, including for loved ones and carers.

Other symptoms can include problems with the bladder, as well as constipation, low blood pressure, restless legs, mood disturbances and sleep difficulties. Not everyone will experience these symptoms but some of them may occur before those related to motor functions such as tremors or muscle rigidity.

Individuals with Parkinson's who experience significant cognitive decline after a year or more of motor symptoms will often be diagnosed with Parkinson's disease dementia, a subtype of Lewy body dementia3.

With a range of over 40 symptoms, Parkinson’s can be difficult to diagnose. For more information, visit Parkinson’s UK to understand the range of symptoms, and how they can progress over time.- How is Parkinson's diagnosed?

If you or someone you care about is experiencing symptoms of Parkinson’s, please contact a GP for an accurate diagnosis and to rule out other conditions.

If the GP thinks the symptoms could be caused by Parkinson’s, they will ask about medical history and symptoms and may carry out some tests to check performance of simple mental or physical tasks. They may also carry out tests to rule out other causes of the symptoms. For example, a patient may initially see their GP as a result of a fall, which may be caused by Parkinson’s or other conditions.

If the GP sees the symptoms of Parkinson’s they should refer the patient untreated to a Parkinson’s specialist, such as a neurologist, for further evaluation. This can include brain scans to help rule out other possible causes. A diagnosis may take some time as there are a number of conditions that may cause similar symptoms. The diagnosis will follow observations and depend partly on how the patient responds to support and medication.

- What treatments are available for Parkinson's?

There are various treatments available to manage symptoms and improve the quality of life of people living with Parkinson’s. In the UK, treatment options include medication, surgery, and supportive therapies.

The most effective medication for Parkinson’s is levodopa. This drug helps alleviate motor symptoms as it is converted into dopamine, which is reduced in the brain of people affected by the condition. It is often combined with drugs called either carbidopa or benserazide, which are used to stop the levodopa being broken down in the bloodstream before it has a chance to get to the brain. It can be used at all stages of the condition.

Dopamine agonists such as pramipexole or ropinirole are another treatment which can be helpful. These mimic the effects of dopamine in the brain and can be used alone or in combination with levodopa. They can be given as tablets, a skin patch or an injection.

Surgical options include device assisted therapies such as deep brain stimulation (DBS). This is when small wires deliver high-frequency electrical stimulation to affected parts of the brain. DBS is usually offered to people who have responded well to treatments but whose needs or condition have become more complex. Additional options include an infusion of duopa or apomorphine to help manage symptoms.

Other therapies such as physiotherapy, speech and language therapy can also be helpful with managing symptoms, as can dietary advice.

More information on treatment options can be found on the NHS or Parkinson’s UK websites.

- How can I get involved in research for Parkinson's?

Parkinson's UK run a Research Support Network (RSN) bringing people affected by Parkinson's closer to research working to develop better treatments. Anyone can join, whether you have Parkinson's or not, allowing you to:

- connect with research and the scientists

- take part in clinical trials and studies

- input into what research is needed and how its carried out

Parkinson's UK also provide a 'Take Part Hub' where you can find the trials most relevant to you, and be connected to studies in your area.

- Support for Parkinson's

Support is crucial, not only for those living with Parkinson’s, but also for their families and carers. Local support groups, charities and online communities can offer valuable help and friendship.

Organisations that can help include Parkinson’s UK, Parkinson’s Care and Support UK, Age UK, Spotlight YOPD and Carers UK.

What causes Parkinson's?

Parkinson’s results from the degeneration of neurons in a region of the brain called the substantia nigra. These neurons are responsible for producing dopamine, which acts as a messenger between the parts of the brain and nervous system that help control and coordinate body movements. As these neurons deteriorate and the levels of dopamine reduce, the characteristic symptoms of Parkinson’s begin to appear. The exact cause of neuronal degeneration in Parkinson’s is not fully understood, which makes it a challenging condition to predict and manage.

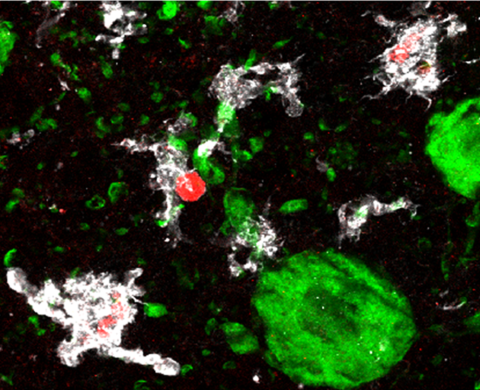

Like other neurodegenerative conditions, Parkinson’s is characterised by the build-up of toxic proteins in the brain – in this case, aggregations called Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites composed of the protein alpha synuclein. Researchers are working to understand why aggregation occurs as it is linked to the death of cells in the brain including the dopaminergic neurons.

Around 15% of people with Parkinson’s have a family history of the condition4, but the exact cause of it remains unknown. At the UK DRI, scientists and clinicians are working to undercover the causes of Parkinson’s.

Several genetic mutations have been identified that are associated with Parkinson's and while specific mutations are rare, having a genetic predisposition can increase the likelihood of developing Parkinson’s, especially when combined with environmental factors.

With evidence suggesting only a moderate heritability of Parkinson’s, environmental factors are thought to significantly contribute to increased risk5. Those explored include smoking of tobacco, traumatic brain injury and exposure to pesticides. At the UK DRI at King’s, Dr Sarah Marzi and her team are interested in determining what biological mechanisms link pesticide exposure to this increased risk for Parkinson’s.

Another avenue of research is seeking to determine which specific cells play a role in the onset or progression of the condition. Prof Caleb Webber, Director of Informatics at UK DRI at Cardiff, and Dr Nathan Skene at the UK DRI at Imperial, use both laboratory and computer methods to help answer this question. This has led to surprising findings including evidence that, as well as the dopaminergic neurons, a supporting brain cell known as an oligodendrocyte is also affected early on in the disease. These results could help target future research efforts and therapeutic strategies.

Recent investigations are looking into the origins of Parkinson’s. Emerging evidence suggests that in some people, Parkinson’s starts in the brain, whilst in others, it begins in the enteric nervous system of the gut. Dr Tim Bartels’ team from the UK DRI at UCL are looking into whether it is possible to detect Parkinson’s in the gut at the very earliest stage, before it has begun to affect the brain.

Early diagnosis would be revolutionary for the treatment of Parkinson’s. Unfortunately, by the time people start to experience symptoms, many of the affected brain cells have already been lost. Research led by Dr Cynthia Sandor, Group Leader at the UK DRI at Imperial, and published in 20236 showed that smart watches could be used to identify Parkinson’s up to seven years before hallmark symptoms appear and a clinical diagnosis can be made. In future, smart watch data could provide a useful screening tool to aid in the early detection of the disease, which would enable people to access treatments before the disease causes extensive damage to the brain.

Other areas of research aiming to support early diagnosis include further development of DaTscans (dopamine transmitter scans), lumber puncture as a diagnostic tool or other blood test and possible genetic links.

We hope that the information gained from these studies will open up the potential to develop new targeted treatments to help individuals living with Parkinson’s disease.

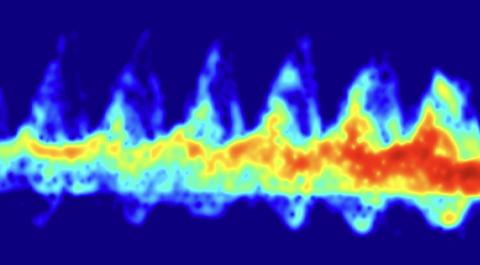

Dr Dayne Beccano-Kelly (Group Leader and UKRI Future Leader Fellow at the UK Dementia Research Institute at Cardiff University) studies communication between brain cells using research models of Parkinson’s. His team are aiming to decipher how miscommunication arises at the earliest stages of Parkinson’s, and find new ways of correcting it before significant loss of cells in the brain, and symptoms appear.

Latest news

Labs working on Parkinson's

Sources & References

- What is Parkinson's? | Parkinson's UK

- Young Onset Parkinson's | Parkinson's Care and Support UK

- Dementia | Parkinson's Foundation

- Parkinson's disease | Medline plus

- Linking environmental risk factors with epigenetic mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease | Nature

- Wearable movement-tracking data identify Parkinson’s disease years before clinical diagnosis | Nature