A study led by Dr Marc Aurel Busche (UK DRI at UCL) reveals a key role in Alzheimer’s progression for oligodendrocytes, as producers of harmful amyloid beta protein in the brain. The research, published in the journal PLOS Biology, could lead to new specific treatments for the condition that exhibit fewer side effects.

What was the challenge?

Accumulation of misfolded amyloid beta is one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s, and reducing levels of this protein in the brain has yielded the first treatments to slow down the disease progression. However, the assumption that neurons are the main source of the misfolded protein has persisted despite being untested.

Oligodendrocytes are responsible for producing myelin, the insulating material that surrounds the projections that transfer electrical impulses between neurons, known as axons. In this study, the team set out to test whether oligodendrocytes produce harmful amyloid beta, and whether they play a role in neuronal dysfunction in early Alzheimer’s.

Our findings suggest that targeting amyloid beta production in just one cell type in the brain might improve early disease outcomes, and could have fewer side effects than the current approach of targeting all amyloid beta throughout the brain.Dr Marc Aurel BuscheUK DRI at UCL

What did the team do and what did they find?

Using post-mortem brain tissue from people with and without Alzheimer’s pathology, the team examined expression levels of genes involved in the production of amyloid beta across different cell types. They first confirmed that oligodendrocytes contained the genes needed to produce the harmful protein. Then, in the tissue from people who had Alzheimer’s, they found an increase in the number of oligodendrocytes expressing genes related to amyloid beta production. Human oligodendrocytes were shown to produce more amyloid beta per cell than neurons.

Next, using mouse models of Alzheimer’s, the team found that amyloid beta produced by oligodendrocytes contributed to the formation of plaques. Crucially, the team were able to restore normal neuronal activity in the brains of the mice by blocking or “knocking out” the production of the amyloid beta protein in oligodendrocytes.

What is the impact?

The findings suggest that targeting production of amyloid beta specifically from oligodendrocytes could be a promising therapeutic strategy for treating Alzheimer’s.

Dr Busche explained:

“Here we have shown that oligodendrocytes produce amyloid beta and that suppressing this process is enough to rescue early dysfunction in mice. This is impactful, as it suggests that targeting amyloid beta production in just one cell type in the brain might improve early disease outcomes, and could have fewer side effects than the current approach of targeting all amyloid beta throughout the brain.”

To find out more about Dr Marc Aurel Busche’s work, visit his UK DRI profile. To keep up to date with the latest UK DRI news and events, sign up to receive our monthly newsletter.

Reference:

Selective suppression of oligodendrocyte-derived amyloid beta rescues neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease

Rajani RM, Ellingford R, Hellmuth M, Harris SS, Taso OS, et al. (2024) Selective suppression of oligodendrocyte-derived amyloid beta rescues neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. PLOS Biology 22(7): e3002727. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002727

Article published: 23 July 2024

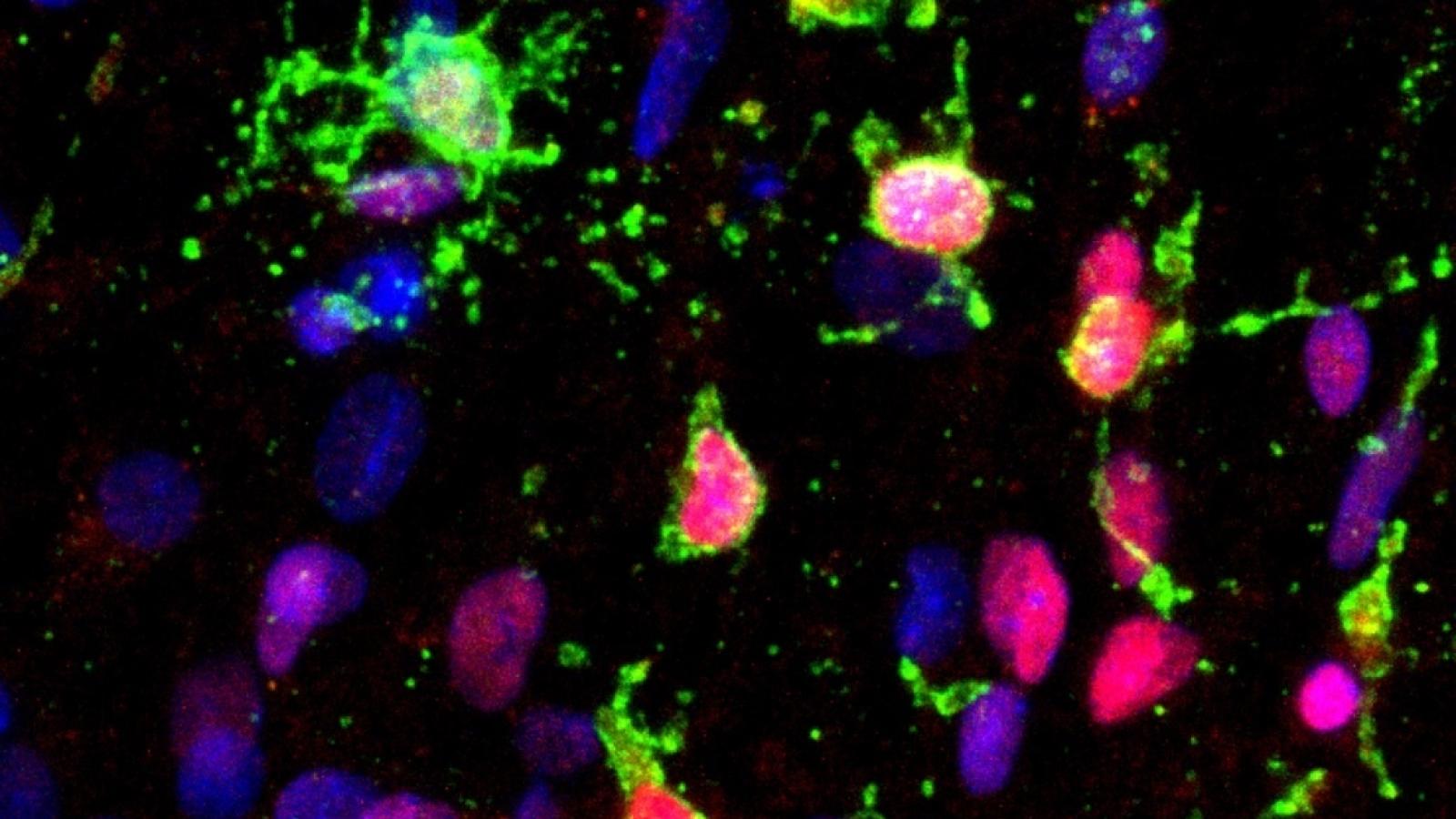

Banner image: Human oligodendrocytes in a dish (green) produce the protein which causes Alzheimer's, credit: Rikesh Rajani